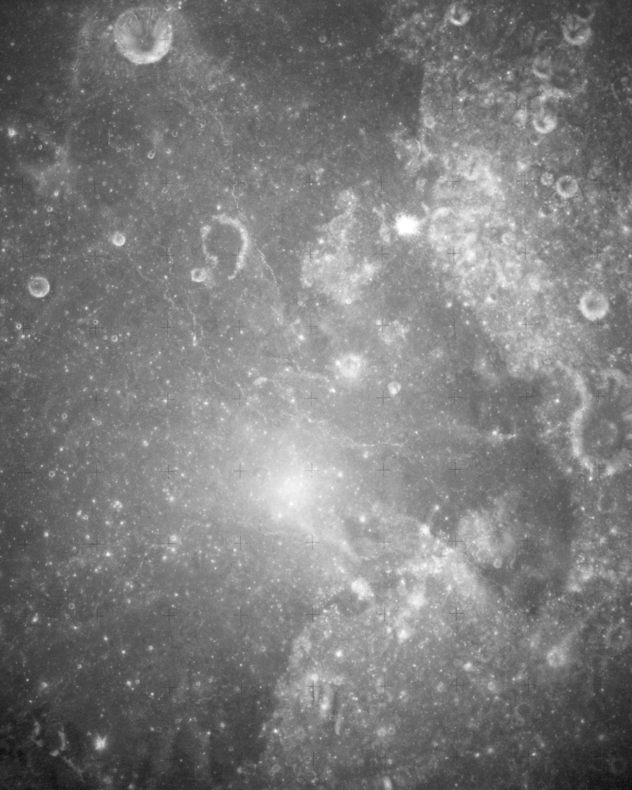

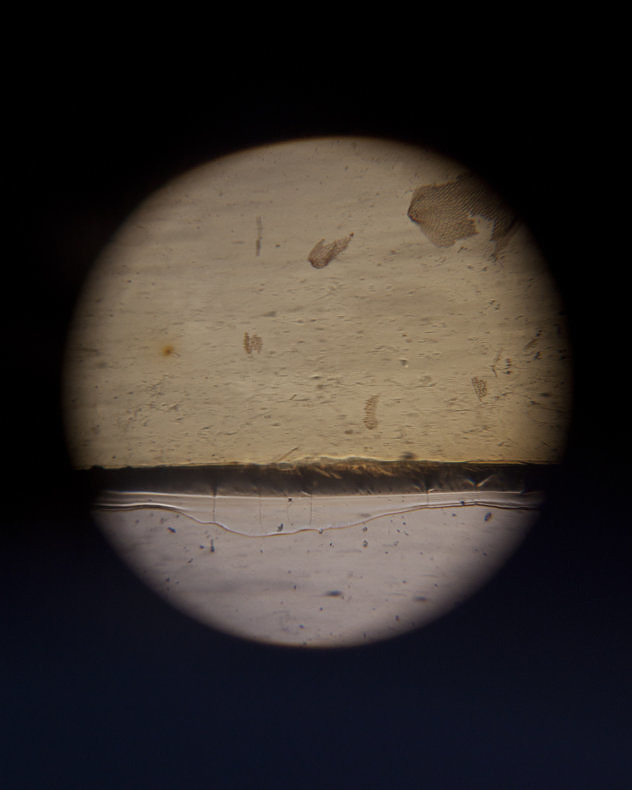

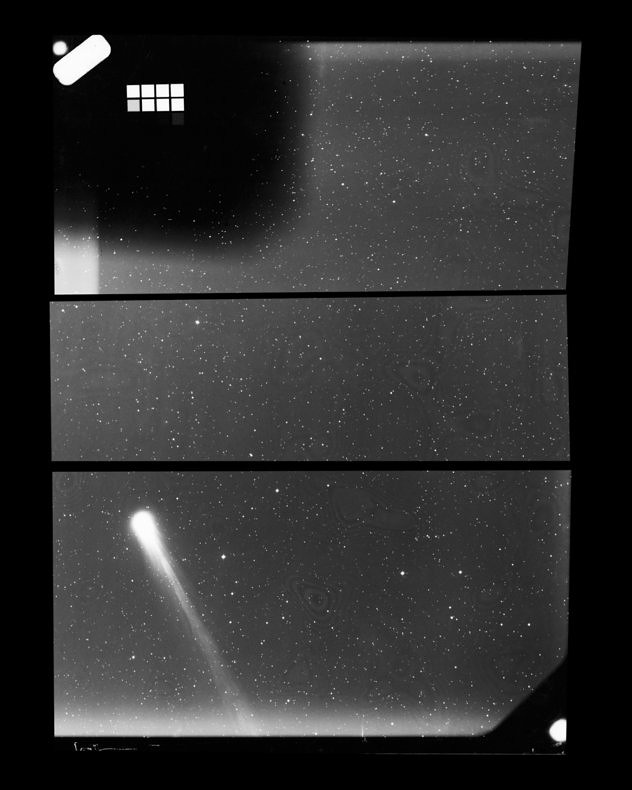

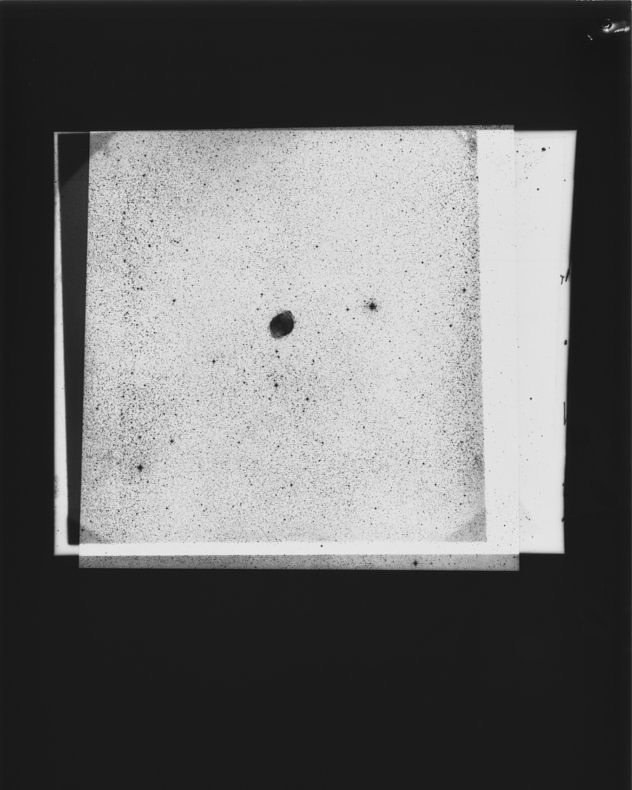

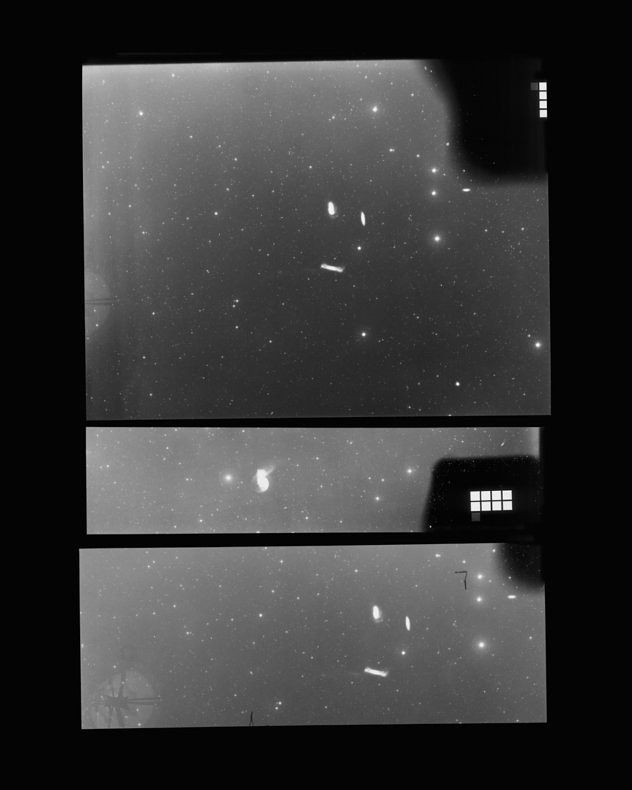

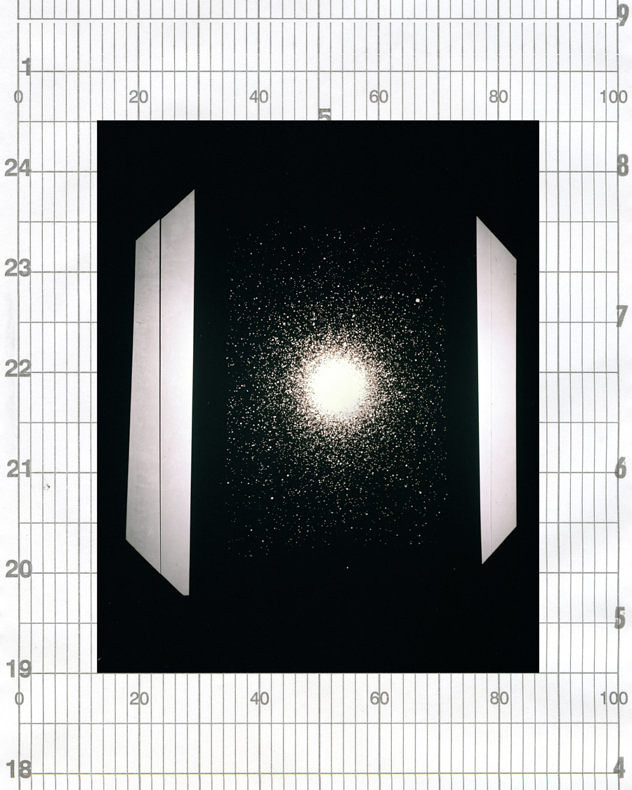

It must have been an instinctive reaction for an inquisitive soul such as inventor Samuel Morse to choose to portray the sky when he took the oldest known photograph of the moon at the dawn of photography in 1839. In following years, the observation of astronomical objects in locations that were favorable to viewing rare and spectacular phenomenon in our celestial sphere, such as eclipses, notably increased. Of those experiences, we have inherited peculiar accounts poised between the adventure novel and scientific discourse. What united the efforts of all the pioneers in the medium of photography was an unfailing belief in the infallibility of mimesis, understood as a tool to access new forms of knowledge. The last few decades have seen the perfection of similar celestial representations – including visual mapping generated by impulse technology detection systems – that has in part done away with the sense of mystery that envelops things we cannot wholly understand. The Big Sky Hunting cycle by Alberto Sinigaglia, on the contrary, goes against this reassuring subordination to reality. It challenges us to reconsider our definition of the concept of vision and our enduring attempts to overcome its intrinsic limits. The works narrate the cosmos through pretense, contradictions and reinterpretation, creating an imaginary idea where the observer goes beyond a purely “retinal” dimension of scrutiny. Therefore, the visual story enacted by the author lacks a predetermined expressive motif, combining shots of reality and existing images that he has appropriated, as well as objects with emblematic value that appear as readymades portrayed through photography. As a consequence, the distinction between reality and fiction looses significance in this investigative terrain, and instead opens the door to osmotic elements lined along a single path that lead to hybridization…

— Carlo Sala

All images ©Alberto Sinigaglia